The Power of Some Men Over Other Men

"What we call Man's power is, in reality, a power possessed by some men which they may, or may not, allow other men to profit by. ... From this point of view, what we call Man's power over Nature turns out to be a power exercised by some men over other men with Nature as its instrument."

Applying some thoughts from an old book (or three) to some contemporary issues around technology.

This is not going to be a typical review post. Instead, I'll mainly share some quotes that stood out from a recent re-read of The Abolition of Man by C.S. Lewis and briefly explain their enduring relevance.

It was written 80 years ago (during the Second World War, and there's a few excerpts where keeping that in mind provides relevant context), but I think it still has useful things to contribute to contemporary debates around emerging technologies, like AI and biotech (I've got a partial draft of a post on the latter, so stay tuned). Major themes of The Abolition of Man include reductionism, education, rightly-formed sentiments, and technologies of social control. It begins with Lewis' thoughts on some negative trends in education in his day, while the third and final chapter is where it most gets into the musings on science and technology that I'm most interested in drawing attention to with this post.

With that brief introduction, let's dive into the quotes.

The task of the modern educator is not to cut down jungles but to irrigate deserts. The right defence against false sentiments is to inculcate just sentiments. By starving the sensibility of our pupils we only make them easier prey to the propagandist when he comes. For famished nature will be avenged and a hard heart is no infallible protection against a soft head.

This relates to the theme that rightly-formed sentiments should be an objective of education.

Until quite modern times all teachers and even all men believed the universe to be such that certain emotional reactions on our part could be either congruous or incongruous to it--believed, in fact, that objects did not merely receive, but could merit, our approval or disapproval, our reverence or our contempt. The reason why Coleridge agreed with the tourist who called the cataract sublime and disagreed with the one who called it pretty was of course that he believed inanimate nature to be such that certain responses could be more 'just' or 'ordinate' or 'appropriate' to it than others.

The first chapter of The Abolition of Man is framed as a response or rebuttal to an English textbook at the time that Lewis felt exemplified many of the flaws of contemporary education. A notion that he spends significant time arguing against is that emotions are purely subjective.

St Augustine defines virtue as ordo amoris, the ordinate condition of the affections in which every object is accorded that kind of degree of love which is appropriate to it. Aristotle says that the aim of education is to make the pupil like and dislike what he ought. When the age for reflective thought comes, the pupil who has been thus trained in 'ordinate affections' or 'just sentiments' will easily find the first principles in Ethics; but to the corrupt man they will never be visible at all and he can make no progress in that science. Plato before him had said the same. The little human animal will not at first have the right responses. It must be trained to feel pleasure, liking, disgust, and hatred at those things which really are pleasant, likeable, disgusting and hateful. In the Republic, the well-nurtured youth is one 'who would see most clearly whatever was amiss in ill-made works of man or ill-grown works of nature, and with a just distaste would blame and hate the ugly even from his earliest years and would give delighted praise to beauty, receiving it into his soul and being nourished by it, so that he becomes a man of gentle heart. All this before he is of an age to reason; so that when Reason at length comes to him, then, bred as he has been, he will hold out his hands in welcome and recognize her because of the affinity he bears to her.

This continues the theme of rightly-ordered affections; it reminds me of a prayer from the Book of Common Prayer that begins, "Almighty God, who alone can bring order to the unruly wills and passions of sinful humanity: give your people grace so to love what you command and to desire what you promise..."

This conception in all its forms, Platonic, Aristotelian, Stoic, Christian, and Oriental alike, I shall henceforth refer to for brevity simply as 'the Tao'. Some of the accounts of it which I have quoted will seem, perhaps, to many of you merely quaint or even magical. But what is common to them all is something we cannot neglect. It is the doctrine of objective value, the belief that certain attitudes are really true, and others really false, to the kind of thing the universe is and the kind of things we are. Those who know the Tao can hold that to call children delightful or old men venerable is not simply to record a psychological fact about our own parental or filial emotions at the moment, but to recognize a quality which demands a certain response from us whether we make it or not. I myself do not enjoy the society of small children: because I speak from within the Tao I recognize this as a defect in myself--just as a man may have to recognize that he is tone deaf or colour blind.

In the preceding excerpt, Lewis introduces what he calls the Tao: objective/universal morality, or a shared sense of the Good between diverse cultures around the world and throughout history.

No emotion is, in itself, a judgement; in that sense all emotions and sentiments are alogical. But they can be reasonable or unreasonable as they conform to Reason or fail to conform. The heart never takes the place of the head: but it can, and should, obey it.

What makes our feelings reasonable or unreasonable.

The operation of The Green Book and its kind is to produce what may be called Men without Chests. It is an outrage that they should be commonly spoken of as Intellectuals. This gives them the chance to say that he who attacks them attacks Intelligence. It is not so. They are not distinguished from other men by any unusual skill in finding truth nor any virginal ardour to pursue her. Indeed it would be strange if they were: a persevering devotion to truth, a nice sense of intellectual honour, cannot long be maintained without the aid of a sentiment which Gaius and Titius could debunk as easily as any other. It is not excess of thought but defect of fertile and generous emotion that marks them out. Their heads are no bigger than the ordinary: it is the atrophy of the chest beneath that makes them seem so.

And all the time--such is the tragi-comedy of our situation--we continue to clamour for those very qualities we are rendering impossible. You can hardly open a periodical without coming across the statement that what our civilization needs is more 'drive', or dynamism, or self-sacrifice, or 'creativity'. In a sort of ghastly simplicity we remove the organ and demand the function. We make men without chests and expect of them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honour and are shocked to find traitors in our midst. We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful.

This is probably one of the most widely known quotes from The Abolition of Man. Some of the ones later on relate more directly to the themes I wanted to discuss in this post, but the paragraph here is justly famous so I'll at least spend a bit of time on it. The 'Green Book' is the pseudonym for the textbook Lewis is criticizing and Gaius and Titius are pseudonyms for the authors; I think by using pseudonyms he's trying to emphasize that he is arguing with certain ideas, not trying to "own" or "destroy" (as in so much contemporary discourse) the people holding them. The ideas he's arguing with comprise a pedagogy that 'debunks' rightly-ordered sentiments instead of inculcating them. It is definitely one of the places where remembering it was written during WWII adds context and emotional weight (especially to the part that I've bolded): in times of necessity, we find that character traits like virtue, enterprise, and honour are highly valuable; education should promote these rather than undermining them.

This passage reminds me of Nassim Taleb's description of people who are "intellectuals yet idiots" and don't even lift.

In actual fact Gaius and Titius will be found to hold, with complete uncritical dogmatism, the whole system of values which happened to be in vogue among moderately educated young men of the professional classes during the period between the two wars. Their scepticism about values is on the surface: it is for use on other people's values; about the values current in their own set they are not nearly sceptical enough. And this phenomenon is very usual. A great many of those who 'debunk' traditional or (as they would say) 'sentimental' values have in the background values of their own which they believe to be immune from the debunking process. They claim to be cutting away the parasitic growth of emotion, religious sanction, and inherited taboos, in order that the 'real' or 'basic' values may emerge. I will now try to find out what happens if this is seriously attempted.

Turning skepticism back on the would-be debunkers.

Telling us to obey Instinct is like telling us to obey 'people'. People say different things: so do instincts. Our instincts are at war. If it is held that the instinct for preserving the species should always be obeyed at the expense of other instincts, whence do we derive this rule of precedence? To listen to that instinct speaking in its own cause and deciding it in its own favour would be rather simple-minded. Each instinct, if you listen to it, will claim to be gratified at the expense of all the rest. By the very act of listening to one rather than to others we have already prejudged the case. If we did not bring to the examination of our instincts a knowledge of their comparative dignity we could never learn it from them. And that knowledge cannot itself be instinctive: the judge cannot be one of the parties judged; or, if he is, the decision is worthless and there is no ground for placing the preservation of the species above self-preservation or sexual appetite.

This is a good description of our need for higher-level principles or axioms to decide between competing desires and instincts.

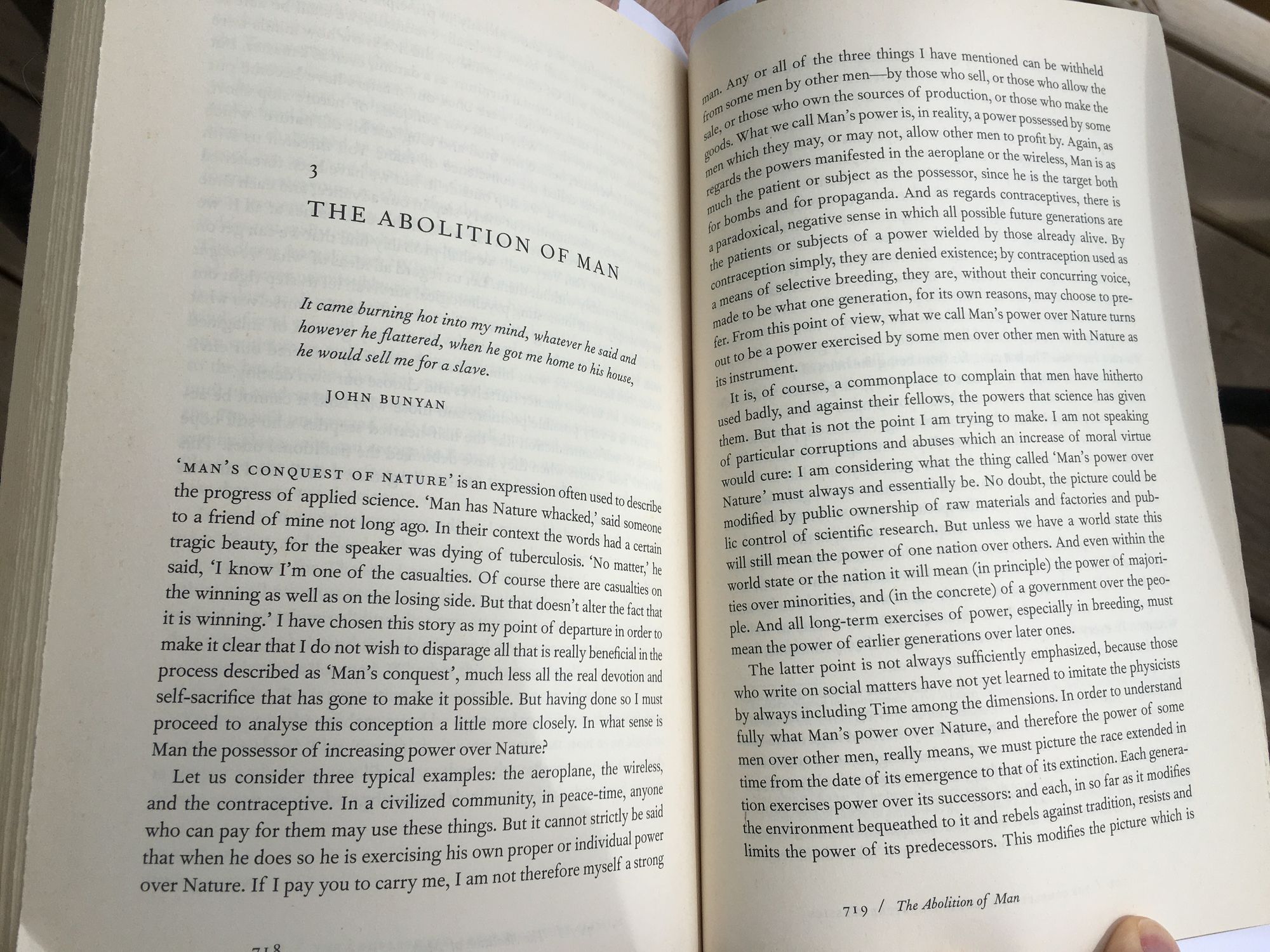

The start of Chapter 3 is central to what I wanted to focus on in this post, so I've included a picture showing the first two pages. I've also excerpted some specific sections in the text that continues below the image.

What we call Man's power is, in reality, a power possessed by some men which they may, or may not, allow other men to profit by. ... From this point of view, what we call Man's power over Nature turns out to be a power exercised by some men over other men with Nature as its instrument.

... And all long term exercises of power, especially in breeding, must mean the power of earlier generations over later ones.

... Each generation exercises power over its successors: and each, in so far as it modifies the environment bequeathed to it and rebels against tradition, resists and limits the power of its predecessors.

Hence the title of this post. This is a profound point about science and technology. Unlocking new abilities as our understanding of the world around us grows can be used for the benefit of humanity in general, and to some extent has been: since The Abolition of Man was published certain diseases such as smallpox have been eradicated, famines are far less frequent, and natural disasters are typically less deadly (due to improvements in early warning, search and rescue, medical care, etc.). On the other hand, only a couple of years after this book was published, the debut of the atomic bomb demonstrated this point (i.e. that applied science could give some people power over others) more comprehensively than Lewis probably imagined when he was writing it. His comment about long-term exercises of power is very relevant to how biotech could affect generations not yet born, although at the time (WWII era, recall) it was probably something more like eugenics that he had in mind.

Man's conquest of Nature, if the dreams of some scientific planners are realized, means the rule of a few hundreds of men over billions upon billions of men. There is neither nor can be any simple increase of power on Man's side. Each new power won by man is a power over man as well. Each advance leaves him weaker as well as stronger. In every victory, besides being the general who triumphs, he is also the prisoner who follows the triumphal car.

I am not yet considering whether the total result of such ambivalent victories is a good thing or a bad. I am only making clear what Man's conquest of Nature really means and especially that final stage in the conquest, which, perhaps, is not far off. The final stage is come when Man by eugenics, by pre-natal conditioning, and by an education and propaganda based on a perfect applied psychology, has obtained full control over himself. Human nature will be the last part of Nature to surrender to Man.

The scientific and technological advances Lewis is most worried about are the ones that empower people—a select few—to manipulate human nature, both biologically and psychologically. Our knowledge of our own biology has advanced leaps and bounds since this book was written, so eugenics is no longer the state of the art. A 'perfect applied psychology' seems much further off (consider the replication crisis, for instance) but maybe that won't matter. I can imagine some AI-driven A/B testing of propaganda that ends up being very effective while remaining a black box.

For the power of Man to make himself what he pleases means, as we have seen, the power of some men to make other men what they please. In all ages, no doubt, nurture and instruction have, in some sense, attempted to exercise this power. But the situation to which we must look forward will be novel in two respects. In the first place, the power will be enormously increased. Hitherto the plans of educationalists have achieved very little of what they attempted and indeed, when we read them--how Plato would have every infant 'a bastard nursed in a bureau', and Elyot would have the boy see no man before the age of seven and, after that, no women, and how Locke wants children to have leaky shoes and no turn for poetry--we may well thank the beneficent obstinacy of real mothers, real nurses, and (above all) real children for preserving the human race in such sanity as it still possesses. But the man-moulders of the new age will be armed with the powers of an omnicompetent state and an irresistible scientific technique: we shall get at last a race of conditioners who really can cut out all posterity in what shape they please.

I like the wry descriptions in this summary of the history of the plans of 'educationalists' (and this excerpt in general fits well with some quotes from other authors I've included below). However, when it comes to fearing an 'omnicompetent state' I have some serious theoretical doubts. There's a case to be made that coherence doesn't scale with complexity, so large and powerful governments often aren't as successful at single-mindedly pursuing a goal. This is not to deny that very real and intense persecution can occur, but there's often an element of wanton stupidity to it (an example that comes to mind is the way Chairman Mao forced peasants all across China to produce steel in backyard furnaces: oppressive? yes; successful? not so much); in contrast, democracies muddle along inefficiently, but seem to yield more achievements on net.

Stepping outside the Tao, they have stepped into the void. They are not men at all: they are artefacts. Man's final conquest has proved to be the abolition of Man.

Yet the Conditioners will act. When I said just now that all motives fail them, I should have said all motives except one. All motives that claim any validity other than that of their felt emotional weight at a given moment have failed them. Everything except the sic volo, sic jubeo has been explained away. But what never claimed objectivity cannot be destroyed by subjectivism.

This is where the title of the book comes from. Debunking or explaining away all values leaves only arbitrary/capricious Whim (the Latin phrase ≈ my wish is my command). Making even our own consciousness quantified and disenchanted will unlock power but at the same time strip away true agency from those at the top.

Their extreme rationalism, by 'seeing through' all 'rational' motives, leaves them creatures of wholly irrational behaviour. ...

At the moment, then, of Man's victory over Nature, we find the whole human race subjected to some individual men, and those individuals subjected to that in themselves which is purely 'natural'--to their irrational impulses. Nature, untrammelled by values, rules the Conditioners and, through them, all humanity. Man's conquest of Nature turns out, in the moment of its consummation, to be Nature's conquest of Man.

This quote and the following one extrapolate the endpoint of a reductionistic worldview.

From this point of view the conquest of Nature appears in a new light. We reduce things to mere Nature in order that we may 'conquer' them. We are always conquering Nature, because 'Nature' is the name for what we have, to some extent, conquered. The price of conquest is to treat a thing as mere Nature. Every conquest over Nature increases her domain. The stars do not become Nature till we can weigh and measure them: the soul does not become Nature till we can psychoanalyze her. The wrestling of powers from Nature is also the surrendering of things to Nature. As long as this process stops short of the final stage we may well hold that the gain outweighs the loss. But as soon as we take the final step of reducing our own species to the level of mere Nature, the whole process is stultified, for this time the being who stood to gain and the being who has been sacrificed are own and the same. This is one of the many instances where to carry a principle to what seems its logical conclusion produces absurdity.

The preceding is a key passage for Lewis' theme in the third chapter of The Abolition of Man, in my opinion. Do we proceed with the conquest of our own human nature?

It is in Man's power to treat himself as a mere 'natural object' and his own judgements of value as raw material for scientific manipulation to alter at will. ... The real objection is that if man chooses to treat himself as raw material, raw material he will be: not raw material to be manipulated, as he fondly imagined, by himself, but by mere appetite...

To retain agency, we have to see ourselves as somewhat distinct from the rest of Nature. The Classical category for mankind was a "rational animal"—above the beasts and below the angels.

Either we are rational spirit obliged for ever to obey the absolute values of the Tao, or else we are mere nature to be kneaded and cut into new shapes for the pleasures of masters who must, by hypothesis, have no motive but their own 'natural' impulses. Only the Tao provides a common human law of action which can over-arch rulers and ruled alike. A dogmatic belief in objective value is necessary to the very idea of a rule which is not tyranny or an obedience which is not slavery.

We need a reference point outside ourselves. Choose your axioms carefully.

I am not here thinking solely, perhaps not even chiefly, of those who are our public enemies at the moment. The process which, if not checked, will abolish Man goes on apace among Communists and Democrats no less than among Fascists. The methods may (at first) differ in brutality. But many a mild-eyed scientist in pince-nez, many a popular dramatist, many an amateur philosopher in our midst, means in the long run just the same as the Nazi rulers of Germany. Traditional values are to be 'debunked' and mankind to be cut into some fresh shape at the will (which must, by hypothesis, be an arbitrary will) of some few lucky people in one lucky generation which has learned to do it.

Another spot where it is poignant to recall that this was published while WWII was still raging.

Perhaps I am asking impossibilities. Perhaps, in the nature of things, analytical understanding must always be a basilisk which kills what it sees and only sees by killing. But if the scientists themselves cannot arrest this process before it reaches the common Reason and kills that too, then someone else must arrest it. ... you cannot go on 'explaining away' for ever: you will find out that you have explained explanation itself away. You cannot go on 'seeing through' things for ever. The whole point of seeing through something is to see something through it. It is good that the window should be transparent, because the street or garden beyond it is opaque. How if you saw through the garden too? It is no use trying to 'see through' first principles. If you see through everything, then everything is transparent. But a wholly transparent world is an invisible world. To 'see through' all things is the same as not to see.

This is an eloquent (when reading a great writer like C.S. Lewis, you appreciate not only what they say, but how they say it) defense of the importance of axioms/first principles. Be careful with reductionist explanations and deconstruction. You wouldn't want to deconstruct something load-bearing, eh?

In this post, I thought I'd also include some notes and quotes from The Law by Bastiat, because they have an overlapping theme with the first part of this post in preserving agency for ordinary individuals.

What are these two issues? They are slavery and tariffs. These are the only two issues where, contrary to the general spirit of the republic of the United States, law has assumed the character of plunder.

Bastiat was not an American, but sometimes an outsider's perspective can provide unique insights. He spends some time in his book (which was written in 1850, before the US Civil War) contrasting property and plunder. Slavery was firmly in the plunder (i.e. illegitimate gains) category for him.

The Law is big on letting collective activity be uncoerced:

We must remember that law is force, and that, consequently, the proper functions of the law cannot lawfully extend beyond the proper functions of force.

He relates the notion in the previous quote to a defense of negative rights:

When law and force keep a person within the bounds of justice, they impose nothing but a mere negation. They oblige him only to abstain from harming others. They violate neither his personality, his liberty, nor his property. They safeguard all of these. They are defensive; they defend equally the rights of all.

The next several quotes remind me of what Lewis wrote about the "Conditioners". These are intellectuals and politicians who feel it is their rightful place to mold everyone else:

To these intellectuals and writers, the relationship between persons and the legislator appears to be the same as the relationship between the clay and the potter.

He doesn't mean it as a compliment that the political theorists he's referring to are fine with ignoring other people's agency.

While mankind tends toward evil, the legislators yearn for good; while mankind advances toward darkness, the legislators aspire for enlightenment; while mankind is drawn toward vice, the legislators are attracted toward virtue. Since they have decided that this is the true state of affairs, they then demand the use of force in order to substitute their own inclinations for those of the human race.

I like the sarcasm in this one.

Oh, sublime writers! Please remember sometimes that this clay, this sand, and this manure which you so arbitrarily dispose of, are men! They are your equals! They are intelligent and free human beings like yourselves! As you have, they too have received from God the faculty to observe, to plan ahead, to think, and to judge for themselves

«Liberté, égalité, fraternité»

Like a chemist, Napoleon considered all Europe to be material for his experiments. But, in due course, this material reacted against him.

Boom!

We shall never escape from this circle: the idea of passive mankind, and the power of the law being used by a great man to propel the people.

The Law might be a bit repetitive on this point, but it is a point that bears repeating. The people at large are not just there as raw material for the schemes and dreams of leaders, political theorists, intellectuals, or organizers.

If the natural tendencies of mankind are so bad that it is not safe to permit people to be free, how is it that the tendencies of these organizers are always good? Do not the legislators and their appointed agents also belong to the human race? Or do they believe that they themselves are made of a finer clay than the rest of mankind?

This one is very reminiscent of a James Madison quote: "If Men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary."

Please understand that I do not dispute their right to invent social combinations, to advertise them, to advocate them, and to try them upon themselves, at their own expense and risk. But I do dispute their right to impose these plans upon us by law -- by force -- and to compel us to pay for them with our taxes.

Like I said near the start of this section, let collective activity be uncoerced.

Finally, a quote from G.K. Chesterton on democracy ties some of these themes together nicely:

This is the first principle of democracy: that the essential things in men are the things they hold in common, not the things they hold separately. And the second principle is merely this: that the political instinct or desire is one of these things which they hold in common. Falling in love is more poetical than dropping into poetry. The democratic contention is that government (helping to rule the tribe) is a thing like falling in love, and not a thing like dropping into poetry. It is not something analogous to playing the church organ, painting on vellum, discovering the North Pole (that insidious habit), looping the loop, being Astronomer Royal, and so on. For these things we do not wish a man to do at all unless he does them well. It is, on the contrary, a thing analogous to writing one's own love-letters or blowing one's own nose. These things we want a man to do for himself, even if he does them badly. I am not here arguing the truth of any of these conceptions; I know that some moderns are asking to have their wives chosen by scientists, and they may soon be asking, for all I know, to have their noses blown by nurses. I merely say that mankind does recognize these universal human functions, and that democracy classes government among them. In short, the democratic faith is this: that the most terribly important things must be left to ordinary men themselves -- the mating of the sexes, the rearing of the young, the laws of the state. This is democracy; and in this I have always believed.

Don't cede everything to experts, or, returning to the technological topics mentioned in my introduction, to AIs/algorithms.