Microstates of a Puzzle

Visual intuition for statistical thermodynamics and information theory.

I've read a few books about thermodynamics and information theory, such as Einstein's Fridge (see review here) and recently The Information by James Gleick (I plan to include a review in one of my posts this year). But reading only takes your understanding so far. You have to work through some examples or view some demonstrations to further internalize things.

My two older children are at an age that they enjoy doing jigsaw puzzles. They are also at an age that the puzzles they do are small enough for the math to be feasible in a spreadsheet. So, one day when I was doing a puzzle with my oldest daughter, I took some pictures at various stages of completion and matched the timestamps up with calculations of the Shannon entropy.

Before displaying the results, I'll explain the calculations I used. Wikipedia summarizes the parallel between statistical thermodynamics entropy (Boltzmann) and information entropy (Hartley):

If all the microstates are equiprobable (a microcanonical ensemble), the statistical thermodynamic entropy reduces to the form, as given by Boltzmann,

S=kB ln W,

where W is the number of microstates that corresponds to the macroscopic thermodynamic state. Therefore S depends on temperature.

If all the messages are equiprobable, the information entropy reduces to the Hartley entropy

H=log |M|,

where |M| is the cardinality of the message space M.

Using base-2 logarithms in the Hartley equation gives the result in shannons or bits. This is what I did below.

In another Wikipedia article, it says that "We can think of [the number of possible microstates] as a measure of our lack of knowledge about a system." Microstates can also be related to degrees of freedom.

When you dump a jigsaw puzzle out of the box, the number of possible arrangements is immense. The pieces aren't all right side up, they could theoretically be placed into the finished puzzle in 4 rotations, and can be arranged into n! (i.e. n factorial) different arrangements. As you work on it, you rule out these possible arrangements until only one is left; the number of possible microstates gets smaller and smaller; you constrain more and more degrees of freedom; you decrease your uncertainty.

Let's make it concrete by looking at photos of a puzzle in various stages of completion.

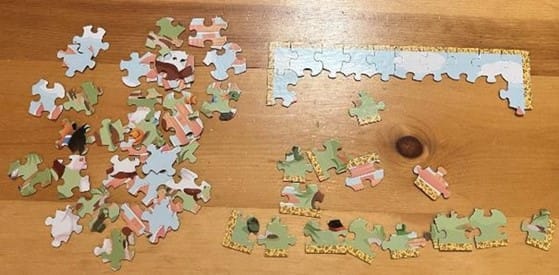

Initially, everything is a jumbled pile. Each piece has 2 possible flipped states times 4 possible rotations for 8 possible orientations. Additionally, there are 60! possible arrangements. These all get multiplied together and then we take the base-2 logarithm:

Log2(860 * 60!) = 452 bits.

The first step a lot of people do when solving a puzzle methodically, is to make sure all the pieces are flipped right side up. This decreases the possible orientations to only 4 rotations per piece:

Log2(460 * 60!) = 392 bits.

This is 60 less than the previous stage because we've removed 1 binary choice across 60 different pieces.

Next, we've separated the pieces into edge pieces and non-edge pieces. Nothing is assembled yet, but this is still a decent reduction in our uncertainty. The perimeter is 28 pieces (leaving 32 pieces in the middle), so we only have to consider permutations of 28 pieces for the pile on the right and permutations of 32 pieces for the pile on the left, which even when they're multiplied together are less than permutations for 60 pieces:

Log2(428 * 28! * 432 * 32!) = 336 bits.

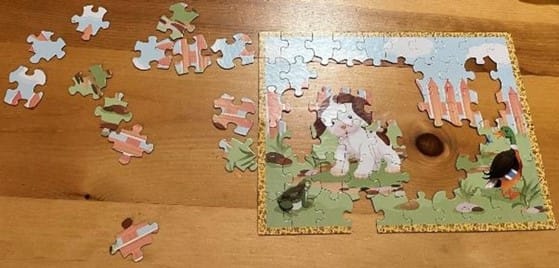

Now the edge is starting to come together. Twelve pieces are attached along the top, with no remaining uncertainty on their location or orientation. That leaves 16 edge pieces still to be assembled, but two of those are corner pieces. They only have 2 possibilities (and the rotation is fixed by which corner is which). The remaining edge pieces are going to be on the sides or bottom, so they have only 3 possible orientations. The pile on the left remains as uncertain as the previous step though:

Log2(2 * 314 * 14! * 432 * 32!) =241 bits.

Now the edge is completed (there is 1 piece missing, but 1 hole once you know where it is doesn't make the math work out any differently). A few other pieces have been attached to it, leaving a pile of 29 pieces with their location and orientation still to be determined:

Log2(429 * 29!) = 161 bits.

Note that around half the pieces have been placed, but two thirds of the uncertainty that we started with has been resolved. The preceding picture is also starting to look and feel a lot more orderly than the one we started with.

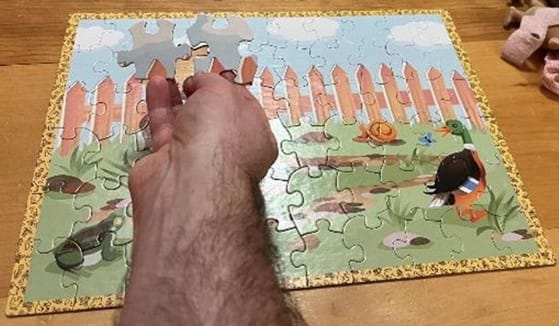

Next, we managed to assemble a couple of larger groups in the centre of the puzzle, but don't have them attached to the edge yet. Their rotation is now known, and the position is narrowed down to shifts of ±1 piece left-right and top-bottom (for a total of 9 positions for each group). Nineteen pieces remain with full uncertainty for their rotation and location (there are only 17 pieces visible in the pile on the left because someone was probably holding a couple ready to place after this picture, or maybe they fell on the floor).

Log2(419 * 19! * 9 * 9) = 101 bits.

Now the puzzle is around 75% complete (there are still a couple of pieces from the pile on the left out of frame). Only 15 spaces are empty (aside from the known hole):

Log2(415 * 15!) = 70 bits.

And only 15% of the uncertainty we started with remains.

Now there are only two pieces left. Their orientation is known, so it's just a matter of which one goes on which side. There's a 50% chance of getting it right the first time:

Log2(2) = 1 bit.

Lastly, here is the finished puzzle. Only one microstate corresponds to all the pieces in an orientation and arrangement that looks like this:

Log2(1) = 0 bits.

I'm also going to go out on a limb and say that this is the only time the Poky Little Puppy has been used in a Statistical Thermodynamics and Information Theory demonstration!

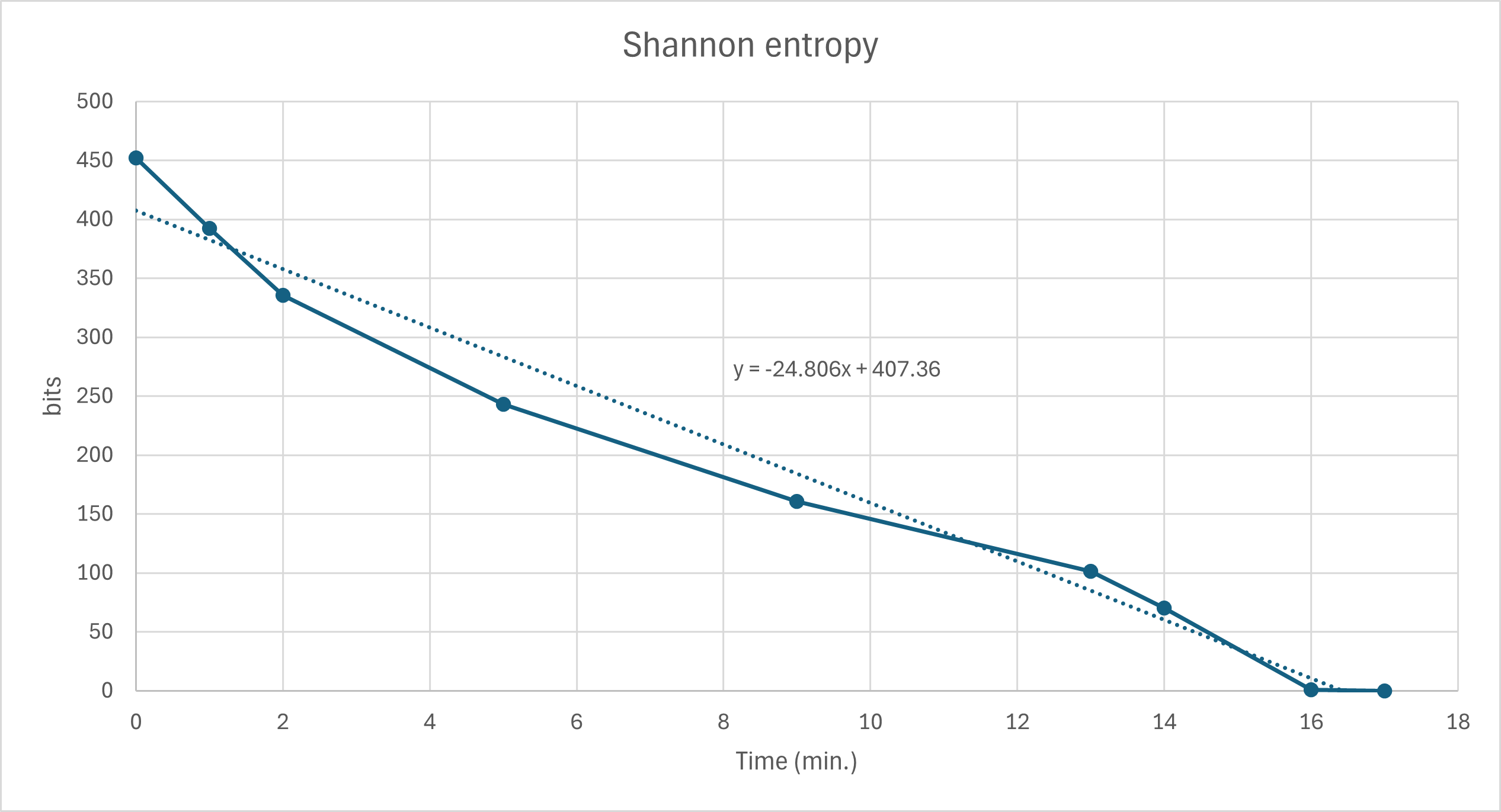

Overall, it took us 17 minutes to complete the puzzle. I made the following graph of the information entropy over time. It went faster in the beginning because upside down pieces and edge pieces are very quick and easy to visually identify. On average, though, we decreased the remaining uncertainty by slightly more than 24 bits per minute. Keep in mind that I was stopping to document the process a number of times and also going at a pace that my preschool daughter could participate; it I'd been optimizing for speed I probably could have done this twice as fast (i.e. 48 bits per minute).

The Second Law of Thermodynamics famously says that entropy in a closed system never decreases. The example of the puzzle that I've used in this post is, crucially, not a closed system. We applied both work and knowledge to get it to a highly-ordered, highly-improbable microstate. The knowledge came from using the cover picture as a template, pattern-matching and analysis skills to determine which pieces fit together, and heuristics from solving other puzzles (e.g. that it's easier to start with the edge).

Can the analysis above provide any insight on other information-processing tasks? Well, I often feel like the process of writing (whether it's a blogpost, a report, or the initial steps I've taken towards a book) feels somewhat like assembling a puzzle. First I have to find the pieces I want—points I plan to make, visuals I want to include, relevant quotes/excerpts, supporting facts or calculations—then I have to work out how to arrange them, and finally fill in additional text to tie it all together. Claude Shannon found that English words have around 12 bits of entropy apiece. Using a speed of 48 bits per minute as calculated above thus equates to 4 words per minute. Now there's no reason to expect different types of information processing to occur at the same rate, and obviously I can write faster than 4 words per minute. However, for the overall process, it doesn't actually seem too far off the mark. A blogpost like this is around 1500 words (a magazine article will often be similar), so a rate of 4 words per minute means it would take 375 minutes, or 6:15. This actually seems like a reasonable estimate by the time you include doing the research, organizing supporting material, thinking it over, writing, and editing.

Although extrapolating to other types of information processing is only going to be a loose approximation, comparing puzzles of different sizes is on much firmer ground. Consider a puzzle 10 times this size (i.e. 600 pieces, assume 20 x 30); the edge alone has 96 pieces, which is over 50% larger than this one. But the information entropy change associated with completing just the edge of the 600-piece puzzle (which is about a sixth of the whole thing rather than almost half) is much larger still:

log2( 496 * (600!/(600-96)!)) = 1066 bits.

Working at the same speed as we did on the 60-piece puzzle, you'd only get a bit over 2 pieces per minute, taking around 45 minutes to complete the edge.