Assorted Links (Winter 2024)

Let's start with a few links related to current events. Scroll down for stuff that's less timely but of more enduring interest if you're reading this page sometime not in the winter of 2024.

- This winter has seen (large and at times intense) protests by farmers in many countries in Europe

- 315 years and 150 km from Abraham Darby's successful use of coke as a fuel for making pig iron, the fires are going out for the UK's steel industry.

- Some unintended consequences of "safer [drug] supply"

- An opinion column on the excessive bureaucratization of contemporary society

- At the intersection of the conflict in Gaza and my profession, I found this news article from a few years ago notable. Apparently Hamas used a lot of pipes that were supplied for water infrastructure as the structure for their rockets. This illustrates one of the challenges with aid: technology is unitary and peaceful applications are often only a step or two away from military ones (not that this is anything new, the exchange rate between swords and plowshares has been recognized since ancient times). The things we associate with modern civilization (such as running water) depend almost as much on trust/cooperation as they do on physical infrastructure.

- The archaeological site of the ancient capital of Saba/Sheba is at risk from the civil war in Yemen.

- What happens when a province defies a federal law? Saskatchewan might be about to test that issue. Meanwhile, south of the border, Texas is trying to take over immigration enforcement from their federal government. I won't be surprised if national unity in both countries continues to be tested in multiple ways in the months and years to come (this is related to Balaji's "American Anarchy" thesis).

An issue I continue to follow is Canadian laws affecting online communications (C-11, C-18, and C-21; C-63 now needs to be added to this growing list). With Bill C-18, the government tried to pressure sites like Facebook to compensate media outlets for linking to them (in contrast to the normal expectation that companies pay to have their links promoted on Facebook); instead, Facebook simply declined to allow links to news in Canada anymore. This was a spectacular own-goal by the Canadian media outlets that lobbied for this bill, further diminishing their audiences. And in spite of massive subsidies for the journalism sector (which is problematic in my view as well for eroding independence from the government), there have been a lot of layoffs over the past ~6 months. Here are some other links on this general theme:

- https://danknight.substack.com/p/the-silent-march-of-trudeau-digital

- https://www.readtheline.ca/p/jen-gerson-do-not-comply

- https://www.michaelgeist.ca/2023/11/bill-c-18-bailout-government-announces-plans-to-pay-for-35-of-journalist-costs-for-news-outlets-with-116-increase-in-tax-credit-per-employee/

- https://www.readtheline.ca/p/peter-menzies-get-ready-to-shut-up

On the general topic of free speech, Nate Silver and Niall Ferguson have worthwhile things to say.

Like Canadian journalism, academia seems like a troubled sector at the moment:

- A record number of journal articles had to be retracted in 2023

- Universities are losing public confidence across the political spectrum

- One minor controversy that's a microcosm of many of the current issues facing academia

What could possibly go wrong as institutions of knowledge squander and erode trust that was built up over centuries right when a new technology (i.e. LLMs) can generate reams of plausible-sounding text—that better be fact-checked before you use it for anything important?

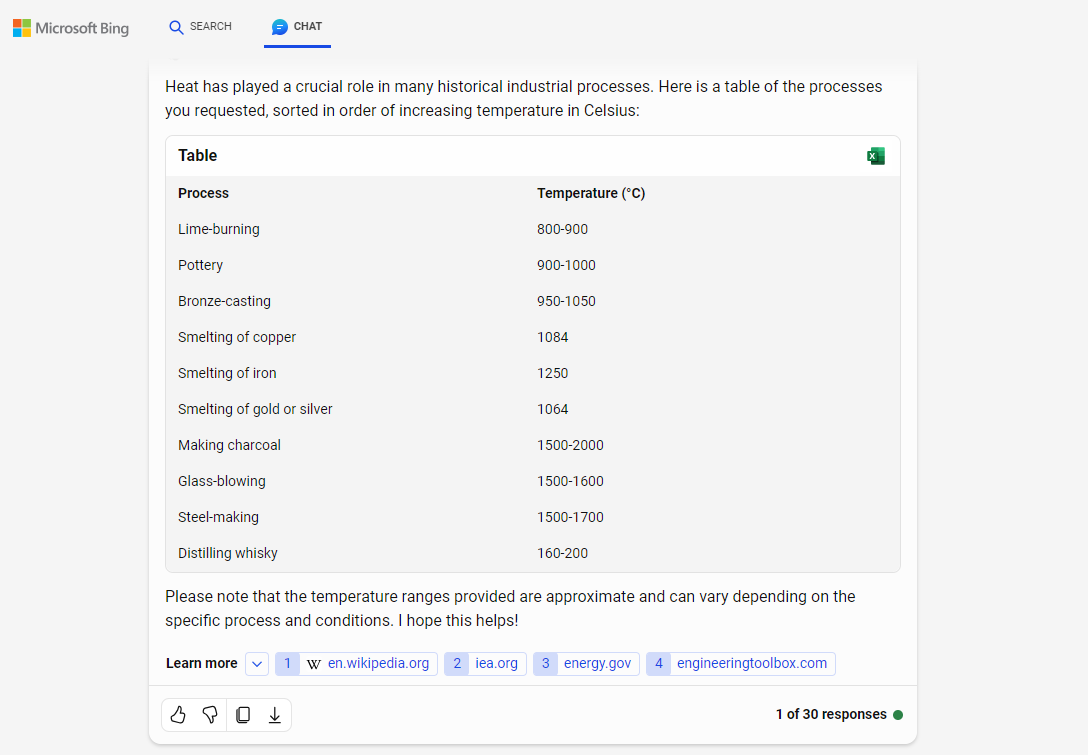

On the topic of AI, the tool I've gotten the best use out of so far has been Bing Copilot for quickly collecting and summarizing information that would previously have taken multiple web searches. The following table is a good example of this: I told Copilot the information I was looking for, and how I wanted it presented. Note that the instruction to sort in ascending order was not followed in spite of the response saying it is sorted—an example of how LLM results are not fully reliable—nor have I fact-checked the temperatures (however, they seem reasonable to me). As part of my writing theme on Industry for 2024, I wanted to explore how the ability to make hotter furnaces or kilns could unlock new materials and processes throughout history. This table illustrates how pottery and objects of precious metal would easily be produced in the Bronze Age (and even the Copper Age). In contrast, glass and steel required higher temperatures than those necessary to enter the Iron Age. Distilling, on the other hand, would have been possible, but to the best of my knowledge, it was unknown in the Classical world.

While we're on the subject of materials and industry: Plastics. Also machine tools. And on a further AI note, here's a graph of the resources that have to go into training these models.

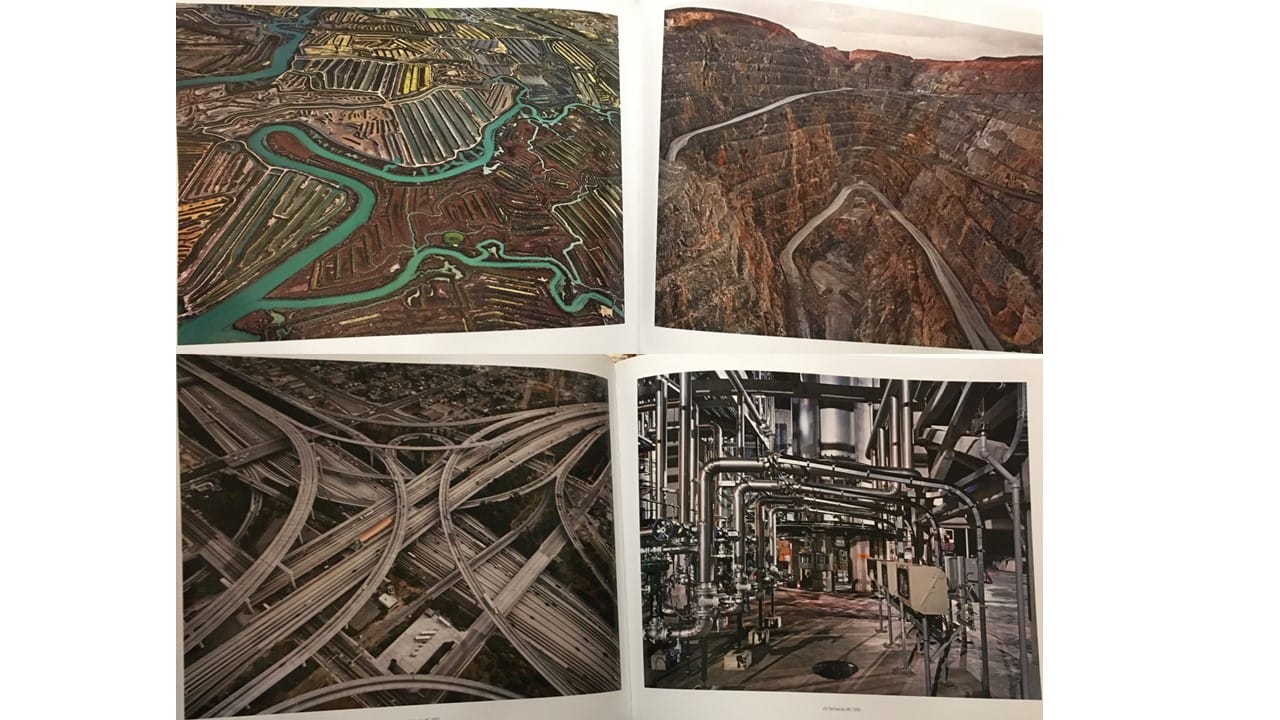

On a completely different computing topic, origami computers are apparently a thing.

For Christmas, I got a book of photographs by Edward Burtynsky. He does a lot of landscape photography of productive and extractive landscapes, factories, and construction sites. Often, the angle they're taken at doesn't show the horizon (or it's very high at least), and some works have striking geometry and bold colour such that they look like abstract paintings at first glance. The impact/imprint of humanity is a common theme. I enjoy looking at these pictures, both the overall image and some of the fine details. I find they give a strong impression of negentropy. Here are a few examples:

This (along with a book I read this winter called Material World—hopefully I'll have a chance to write about it a bit later this year) made me revisit and further develop an idea I mentioned towards the end of this post. Consider some of the most complex modern artifacts like oil refineries and computer chips. They have very high packing densities, fitting hundreds of kilometers of pipe or billions of transistors and other components into a compact area. Visually and conceptually, they're reminiscent of space-filling curves (e.g. Hilbert); linear features (i.e. pipes and circuits in these examples) indeed end up with a fractal dimension that's probably closer to 2 than to 1. (We could also find examples at higher dimensions, like packing a lot of usable surface area into 3D space). These things are fractal-like in some ways, but not perfect/regular fractals. The fact that they're aperiodic makes them incompressible in an information sense. These highly specific and ordered arrangements of matter are local concentrations of negentropy (total entropy in the system still increases, of course, as both of these examples export a lot of entropy) that can bring a lot of order to bear on their inputs: separating crude oil into numerous constituent products, and sorting or doing other calculations on data. This observation generalizes really well: a compact yet ordered packing of a linear feature suggests a really productive locality. Other examples that have come to mind are the dense road networks of major cities, the windings of copper coils in generators, and even DNA (over 2 m is packed into the nucleus of each of our cells). Even something like terracing reflects this, as it greatly increases the usable flat surface area.

We've now reached the section of this post where I wanted to share some thought-provoking essays.

- An interesting in-depth look at the business of check (or cheque, if you prefer) cashing

- On the limitations of modelling (something I've written a bit about before too)

- The Sabbath as restoration rather than restriction

- Contrasting some themes in Dune and Foundation.

- Categorizing different "social system[s] that accumulate wealth and invest it into further production"

- On the value of agency and why education should involve doing real things

- The legacy of the civil service exam for dynastic Chinese scholar-bureaucrats. Also on the subject of Chinese history, this account of the legacy of the Opium Wars.

- Vitalik Buterin's balanced take on techno-optimism:

The Chinese proverb 天高皇帝远 ("tian gao huang di yuan"), "the sky is high, the emperor is far away", encapsulates a basic fact about the limits of centralization in politics. Even in a nominally large and despotic empire - in fact, especially if the despotic empire is large, there are practical limits to the leadership's reach and attention, the leadership's need to delegate to local agents to enforce its will dilutes its ability to enforce its intentions, and so there are always places where a certain degree of practical freedom reigns. Sometimes, this can have downsides: the absence of a faraway power enforcing uniform principles and laws can create space for local hegemons to steal and oppress. But if the centralized power goes bad, practical limitations of attention and distance can create practical limits to how bad it can get.

With AI, no longer. In the twentieth century, modern transportation technology made limitations of distance a much weaker constraint on centralized power than before; the great totalitarian empires of the 1940s were in part a result. In the twenty first, scalable information gathering and automation may mean that attention will no longer be a constraint either. The consequences of natural limits to government disappearing entirely could be dire.

Digital authoritarianism has been on the rise for a decade, and surveillance technology has already given authoritarian governments powerful new strategies to crack down on opposition: let the protests happen, but then detect and quietly go after the participants after the fact. More generally, my basic fear is that the same kinds of managerial technologies that allow OpenAI to serve over a hundred million customers with 500 employees will also allow a 500-person political elite, or even a 5-person board, to maintain an iron fist over an entire country. With modern surveillance to collect information, and modern AI to interpret it, there may be no place to hide.

(This covers some of the same ground that I tried to touch on in this post).

Finally, some random stuff that didn't fit anywhere else:

- A flowchart for estimating the year a map was published

- When I read Pascal's Pensées a couple of years ago, one part that stood out to me was his thoughts on politics. He promotes how making power/status more legible can decrease conflict. Here's a post (in French) on this topic. Also a very niche meme (not my own work):

- Some fun demographic analysis of the Shire and Middle Earth. And something similar for the real world.

- "Are mental health awareness efforts contributing to the rise in reported mental health problems?" Somewhat related.

- Martin Luther's influence on Christmas traditions.

- How the decline in public order and social trust are part of why we can't have nice things.

- A map of key cropland regions around the world.

- An important lost wetland on the shores of Lake Erie.

- Some DIY home laboratory tips and tutorials

- The role of mathematics and accurate measurement in the Industrial Revolution (I'm just finishing reading a book on this topic of precision, so stay tuned for more on this topic)

- Some advice for digital privacy.