Baie des Chaleurs' industrial patrimony

The category of things that must exist as a going concern or not at all

A photo essay. Originally I wanted to go to these sites and take my own photos, but that didn't work out timing-wise last year, so the photos are a curated collection from Google Earth and news articles. I didn't want to put off writing this waiting for photos, because this is a very timely topic. Not only is it a continuation of my series on industry and supply chains and related topics, but it is also directly relevant to re-shoring attempts and trade/tariff disputes.

The Bay of Chaleur coastline in northern New Brunswick used to have a significant amount of heavy industry relative to its population. It had/has some notable advantages, such as better rail access than most of the Maritimes and a deep water port at Belledune. However, in the previous decade or two a lot of this went away. Trying to understand the past can contribute to planning for the future of industry, in this region and elsewhere in Canada.

Bathurst

Bathurst is a small city that was formerly home to a large pulp and paper mill. It went through various owners during its years of operation, but at the time it ceased production in 2005 it was owned by Smurfit-Stone. During the past twenty years, the site went through additional owners but did not get cleaned up or redeveloped. Finally, last year the provincial government took ownership after there were no takers at a tax auction. Some of the remaining long-delayed demolition work is now underway.

Here's a photo of what the mill looked like when it was still standing, followed by one showing the condition the site has been in in recent years:

Next, here is a photo of some demolition in progress.

I also grabbed some screenshots from Google Earth from when the site was still standing (no longer in operation, but no demolition had occurred) followed by its condition in recent years (until site clean-up resumed in late 2024). Of special interest to me are the two UASB reactors for treating wastewater from the plant, near the centre of the image along the river.

This paper mill closure was not the only one in the province to face closure. The Dalhousie one will be covered in a later section of this post; both it and Bathurst are in this alphabet of closed P&P mills in Canada. Additionally, there was the Repap/UPM mill in Miramichi (formerly known as Newcastle, and around 70 km south of Bathurst) that closed in 2007. At the head of the Bay of Chaleur, the mill in Atholville had closed in the 1990s, but reopened under the ownership of the Aditya Birla Group (in 1997), which also happened with the mill in Nackawic (in the western part of the province) around a decade later in 2006.

Also in the Bathurst area (just over 20 km to the southwest) was Brunswick Mines. This zinc and lead mine was in production from 1964 - 2013. The metal from this mine was smelted in Belledune, as described in the next section.

Belledune

Belledune is a tiny village, but it has a deep water port and a thermal power plant, which gives it good industrial potential. The big industry there was a smelter. It continued operating (on ore brought in from elsewhere) after Brunswick Mines ceased production, but shut down in 2019. This followed a months-long labour dispute and the cancellation of an upgrade project. In the present context with the rising importance of batteries and threatened tariffs from the United States it is worth noting that a lot of the lead smelted here was exported to the US for battery manufacturers, and after it closed there were only two lead smelters in North America left, one in British Columbia and one in the Mexican border state of Coahuila.

The coal-fired power plant in Belledune is still operating, but it is slated to shut down in 2030. See this graph 3/4 of the way down the page from a post I made several years ago showing the impact of its closure on power generation capacity in the province: the red segments of the bars show what will be lost when it closes in 2030 instead of its earlier plan of running until 2040.

Demolition and site rehabilitation of the smelter is currently in progress. Here is a picture of the Belledune waterfront, with the smelter in the foreground and the power plant in the background:

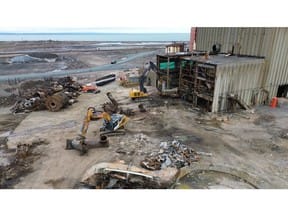

Here is a picture of some of the demolition work:

And here's a good satellite image of the smelter site from Google Earth from back when it was in operation (note the full parking lot):

Belledune has not given up on industry. There was an attempt to bring in an iron-ore processing plant (Maritime Iron Inc.) around the same time the smelter closed down. However, this fell through after NB Power pulled out of a partnership because of concerns the project would be affected by the federal phase-out of coal in 2030 (iron smelting consumes coal, at least with conventional methods) and that greenhouse gas emissions from it would be attributed to NB Power and require raising rates for all their customers (to pass on the costs of the carbon tax). David Campbell points out that this project could have re-shored some iron processing to North America from Asia and laments what could have been:

I’ve heard politicians bragging about New Brunswick’s reduction in carbon emissions. They are less quick to tell people this has come by closing industrial plants and from among the weakest economic growth among the 60 U.S. states and Canadian provinces since 2008. I might have snarkily remarked the best way to reduce your carbon emissions is to shut down your province.

Again in the present context of a trade showdown with the United States, having a stronger domestic supply chain for iron and steel would be an advantage right about now.

Belledune does still have its port. They do a brisk trade in biomass (wood pellets) and are hoping to get into green hydrogen. That is a similar idea to what Stephenville NL is planning. Frankly, I'm skeptical of trying to plop such a challenging industry into places that don't have a robust chemical processing cluster already. Hydrogen is challenging to store and transport, so having off-takers in close proximity is a big advantage. Having a large operator labour pool and constellation of contractors with relevant skills is also useful. I wish them well, but I think these small communities would have a better shot pursuing industries that play to their strengths (e.g. processing resources that are sourced nearby, or dealing with something that is shipped in bulk in the case of Belledune with its port having experience with that).

Dalhousie

Dalhousie is a town near the inner end of the bay that also had a large pulp and paper mill: International Paper, later Abitibi-Bowater. It closed in 2008. According to Wikipedia, it had produced 640 tonnes per day of newsprint.

Here is a historical photo of when this mill was in full operation:

There was also a 315 MW generating station in Dalhousie. It burned Orimulsion, which was sourced from Venezuela. (Important parenthetical: despite Canada being a net exporter of oil and gas, power plants and refineries on the east coast import it from abroad due to limitations in infrastructure for moving this resource within the country). The political situation there led to them ceasing to sell this fuel to Canada in 2006 (and no new supply contracts after 2004). Decommissioning of the plant started in 2013. Some elements—just the tank farm as far as I can tell—are still a work in progress, but the dramatic moment came in 2015 when the power plant and its smoke stacks were demolished. The first attempt at demolishing the power plant did not bring down the stacks, as caught on video here:

They did come down on a second attempt later that year (2015). Here is a picture of that power plant before it was demolished:

Here are some screenshots from Google Earth of the generating station and the paper mill sites in 2009 and 2024, respectively. The sites have mostly been levelled (aside from a tank farm at the generating station), but they have not been redeveloped. The town would like to pivot from industry to "investing in tourism, arts and culture".

There was also a chloralkali plant on the west end of Dalhousie (shown in the Google Earth screenshot below) which also ceased production in 2008.

General Thoughts

So in summary, this region had closures of half a dozen industries or power plants between 2005 and 2019. It also had a billion dollar project (i.e. Maritime Iron Inc.) fall through. And another power plant is scheduled to shut down in 2030. These closures are a tough blow for a relatively small region (in 2016 the combined population of Gloucester and Restigouche counties, which encompass the Bay of Chaleur coastline plus some adjacent areas, was only around 109,000 people). And as I said in the introduction, this is a region that has some features that should help it to attract and retain industry. So what went wrong? I don't know the deep background of each of these closures, but there are some potential factors that jumped out at me from the research I did for this post:

- Mines running out of economically-exploitable ore is an expected outcome. A facility like Brunswick Mines has a finite lifespan. So that one is not hard to explain. But then it has a domino effect, where the raw materials no longer being available locally raises the operating costs of the nearby smelter in Belledune. It probably also affects a bunch of ancillary/support businesses, weakening the industrial ecosystem in the area, but there's less visibility on that.

- In the neighbouring province, the premier has talked about "taking the 'no' out of Nova Scotia". Processing resources from nearby is going to be just about the most reliable basis for industry under most circumstances.

- In the case of Dalhousie's paper mill, there was declining demand for their product (i.e. newsprint). In contrast, the mill in Atholville that was able to reopen pivoted to producing dissolving pulp to export as a feedstock for producing the textile viscose.

- The generating station in Dalhousie had bad luck with its fuel supply. When it switched to Orimulsion in the 1990s I don't think anyone could foresee the turn Venezuela would take.

- Several of these processes are very energy-intensive: smelting and chloralkali for sure, and pulp and paper to a lesser extent. Power generation in northern New Brunswick (and the province as a whole I think) has declined. The closure of the 315 MW power plant in Dalhousie was less than half offset by two wind farms along Chaleur (at Caribou and Lameque) totalling 144 MW; the planned closure of the 450 MW power plant in Belledune in 2030 will further this decline in capacity.

- For comparison/contrast, Quebec uses plentiful and cheap hydroelectricity to do a lot of aluminum smelting north of the St. Lawrence River.

- The declining population of the region (population of Dalhousie peaked in the 1970s) leads to a smaller pool of skilled workers.

- Asia, especially China, becoming the workshop of the world increased competition on materials processing done elsewhere.

I fear that once industry has gone away, it's hard to get it spun back up. I commented in a discussion elsewhere about vital infrastructure that,

Something I got thinking about during the Covid lockdowns was that there's a whole category of things that exists as a going concern or doesn't exist at all. Too much relies on tacit knowledge (even when you're very diligent about documentation) and personal relationships that keep things running more smoothly. Like air travel got a lot worse than it used to be from getting curtailed long enough that the workforce lost its muscle memory. Or, having been to a couple of refinery sites, restarting one after it's been offline for even a few years strikes me as almost as big of a challenge as building a new one.

Someone else had a thought-provoking reply:

Yep. Stop making jet engines or nuclear plants or microprocessors or whatever for a decade, and you're likely to find it very hard and expensive to restart--some of your employees are gone, most of the rest have forgotten a lot, and there's not a working community of people keeping some kind of continuity of operations and institutional memory.

Some [scifi] stories postulate people redeveloping technology from books, but I think they very often underestimate how much critical knowledge isn't written down, and often can't be written down.

People who have worked in well-functioning refineries/chip fabs/software houses/construction projects/aircraft carriers/surgical clinics/car repair shops/etc. have a lot of implicit knowledge about how things worked and how they should feel, the "lore" that goes with the book knowledge on how to do those things, the kinds of problems that came up, and so on. Individual practitioners know stuff like how some machine should sound when things are working right, or what the process smells like when things are going okay, or how hard you have to twist that particular bolt to get it tight enough but not strip it, or whatever.

There's a balancing act to be struck, however, in keeping industry a going concern in a certain geography while not propping up sluggish firms or obsolete sectors; allowing failure is a crucial part of properly allocating resources, as this article points out:

In the words of the economist Joseph Schumpeter, “[T]he problem that is usually being visualized is how capitalism administers existing structures, whereas the relevant problem is how it creates and destroys them.” If the government were willing to let big businesses die a natural death when their time comes, then these resources would be captured by better-managed firms, and our industrial and technological growth would proceed faster.

I hope that at least some of these industrial sites in the Chaleur region that have been swept bare can eventually hold productive new industries.