Two Rivers in Asia

Travel, geopolitics, and water—this post is a review of two books that sit at the convergence of several of my interests. It can also be seen as the inland accompaniment to this post covering coastal areas in the same general region.

The River at the Centre of the World: A Journey Up the Yangtze, and Back in Chinese Time by Simon Winchester and The River's Tale: A Year on the Mekong, by Edward Gargan both are travelogues of trips on East Asian rivers that the authors took in the 1990s. These were used bookstore finds (by my wife), but even though it has been decades since they were written, I feel that their subject matter is as timely as ever (in part because they show how much that region has changed since then, but for many other reasons as well). Between these two books, I enjoyed Simon Winchester's more. Gargan's style was too florid and baroque for my tastes, and he also has less of a sense of some of the technical details (about boats and river stages) that left me wanting. Both authors were journalists with a lot of experience reporting from Asia. Simon Winchester, for example, was based in Hong Kong for over a decade (before the handover).

The Yangtze basin has an area of 1,745,000 square kilometers and an average flow of 76,365 million cubic metres per month. In June, the monthly discharge reaches 136,756 million cubic metres. It is one of the top five rivers in the world by flow. The Mekong sits just outside the top ten, with an average flow of 41,100 cubic metres per month from a watershed area of 787,260 square kilometers. Its peak monthly flow comes in September and is 108,000 million cubic metres. Both rivers have their minimum monthly flow in February; the Yangtze falls to 27% of its average flow, while the Mekong falls to 1% of its average flow. (These stats come from the same source as I used in this post, which also mentions both of these rivers).

Before getting into the books, I want to share some useful geographical context. Both of these rivers arise in the Tibetan plateau—as do a number of other highly-important rivers in Asia. Between regional rivalries (especially between India and China), the politics of water resources (witness the turmoil around Ethiopia's new mega-dam), and the upcoming (uncertain timing, but soon in actuarial terms) succession of the Dalai Lama, this could be a very contentious region in the years ahead.

As seen in the above map, the Yangtze and Mekong run very close together in mountainous western China. In fact, they are only 50 km apart at their closest proximity, and the Salween and Irrawaddy aren't far away either. These short distances between major rivers (all rank within the top dozen on the continent) really makes one wonder if water transfer/diversion project (dams and tunnels) have been considered between them—a high-stakes move, to be sure, but in view of how stressed water resources are there, I'm not sure it can be ruled out that someone would attempt it. This area where the Yangtze, Mekong, and Salween run in parallel, steep-sloped valleys is reputed for its natural beauty and is protected as a UNESCO heritage site and a Chinese national park.

Another thing to note about the geographical context is the population density. Almost half a billion people live in these two watersheds. However, the distribution is far from uniform. The full length of the Yangtze River lies within China, and it crosses the Heihe-Tengchong line on its journey to the sea. Well over 90% of the population of China lives to the east of this line; the upper Yangtze watershed and other areas to the west are very sparsely populated in comparison to central and coastal parts of China. The Mekong is a trans-boundary river (it flows through and/or forms part of the border of China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam), but has a similar dynamic with the densest population in its lower reaches.

These aspects of the geography certainly show up in the books. The main body of this review will be organized geographically, so the above context should be kept in mind. I'll start at the mouth of the Yangtze and cover some parts that stood out from The River at the Centre of the World, then pivot and follow the Mekong past significant places from The River's Tale. This approach follows the direction of travel of Winchester and Gargan, respectively. Note that their paths crossed (albeit a few years apart) in the upper watersheds. Both authors visited Lijiang (on the Yangtze) in Yunnan and Chamdo (on the Mekong) in Tibet, because they are significant settlements close to both rivers. Simon Winchester made his trip in 1994 (but noted some things that had changed in the interim period in the second edition from 2006) and Edward Gargan made his trip in 1998.

To help keep myself oriented as I was reading, I put some placemarks in Google Earth showing locations mentioned in each book. The first one is looking southeast from the Tibetan plateau, while the second is a more normal orientation with North at the top:

Having taken care of some introductory material, on to the books! I'll be focusing on impressions and interesting facts that stood out to me while I was reading, along with themes and trends that seem significant (especially with the benefit of 2+ decades of further developments to compare to) in a geopolitical sense.

The River at the Centre of the World actually starts in New England. Winchester visited an elderly man whose family had fled China in the first half of the 2oth century (as so many did) to see a priceless painted scroll in his private collection. This scroll is 53 feet in length and depicts the entire length of the Yangtze River. Seeing it was part of what inspired him to take this journey. The subtitle of the book, A Journey Up the Yangtze, and Back in Chinese Time, alludes to the fact that the pace of modernization and industrialization had been much faster in coastal China compared to the interior of the country, so a journey upriver was—at the time!—akin to seeing how things used to be in the country as a whole.

Simon Winchester describes how the Yangtze river divides China like a belt (North versus South) but also unifies the civilization. He notes that not only is it the heartland of Chinese civilization (although the centre of political power has often lain elsewhere, as it currently does), but is globally significant, with around 1 in every 12 of all people living in the watershed.

On his journey, he started from Hong Kong and travelled by ship to the estuary just east of Shanghai, so he could enter the river properly. He noted that the Spratlys and Paracels were just becoming an issue at that time. Even back in 1994, there were 1,000 ships per day passing through the mouth of the estuary. Shanghai is now the busiest port in the world. That initial trip by boat from Hong Kong to Shanghai was a very fitting way to begin the journey, as competition between these two cities is a major theme of the book. He predicted that Hong Kong would be eclipsed after the handover (basically playing the New Orleans to Shanghai's New York, i.e. as a gateway primarily to the south instead of the pre-eminent port of China) due to Shanghai's strategic location at the mouth of "the river at the centre of the world". Even back in colonial times, there was a recognition of Shanghai's value:

Shanghai was no isolated trading port like Canton or Macau, merely suspended on the underbelly of China, cut off from the vastness of the Empire by ranges of hills and linked to it only by moody and irritatingly short rivers. Shanghai, rather, was at the downstream end of the Yangtze, a river that, though then quite unexplored by foreigners, clearly penetrated deep into the heartland of the nation.

One detail that Winchester mentioned as he travelled upriver was about the severely endangered (possibly extinct in the years since he wrote his book) Yangtze dolphin. It used to be associated with a goddess, but after the Great Leap Forward that tried to erase old superstitions, they started to be hunted. With devastating effects.

As I mentioned above, one of the things that I appreciated about Winchester's writing is that he seemed attuned to technical details, such as quantifying tidal ranges or flood stages at various locations. Here is his description of the Yangtze's hydrology, which shows why flooding is such a threat:

[China's] cross section, for example, is dramatically unlike any other on earth. China's western side is universally high--an immense melange of contorted geologies that involve the Himalayas, the Tibetan Plateau, and the great mountain ranges of Sichuan, Yunnan and Gansu. Her eastern side, on the other hand, is flat and alluvial and slides muddily and morosely down into the sea. The country in between is far from a smoothly inclined plane, of course, but the difference in altitude between her western provinces and the sea is so vast--involving four and a half miles of vertical drop--and the trend of the slope so unremitting that anything which falls on her western side, be it snow, hail, torrential rain or the slow gray drizzle of a Wuhan autumn afternoon, will roll naturally and inevitably down to the east.

Her two greatest rivers, the Yellow River and the Yangtze, flow in precisely that direction--west to east. They take this runoff from the high Himalayas and the other ranges and then, capturing river after river along the way--all of which do just the same, scouring their source mountains for every drop of water they can find--they cascade the entire collected rainfall from tens of thousands of square and high-altitude miles down into the earth-stained waters of the East China Sea.

Additionally, the precipitation is highly seasonal due to the monsoon. These factors combine to make epic floods possible. However, he does have a theory (slightly on the conspiratorial side) that the Beijing government exaggerated reports of flooding during his 1995 trip, as what he was seeing on the ground (or on the river, rather) didn't look as bad or as widespread as what the news was depicting; their alleged motivation for this kind of exaggeration (if that's what it was—my home city has also experienced floods and it might not look like much if you go several blocks away from the waterfront, but having key arterial streets submerged is a genuine impact) was to build support for the 3 Gorges Dam under construction it the time (a topic I'll return to below).

One of the big cities along the river in central China (but still in the lowlands before any dams are reached) has gained global notoriety in recent years since the publication of The River at the Centre of the World: Wuhan. So I read the chapter or two that Winchester spent there with great interest. Wuhan is a tri-city at an important junction on the Yangtze. It was where early rail lines crossed the river so it became an intermodal hub. And it was where the Railway Protection Movement broke out in 1910, leading to the rebellion that toppled the Qing dynasty. The city's revolutionary bona fides are further bolstered by a famous swim that Chairman Mao took there. Simon's guide, Lily (not her real name, for obvious reasons), was vocal about her feelings for Wuhan:

"Wuhan people are different," she said. "I don't like them at all. I don't like the city--a very dirty place, very bad people. But they think they are special. They are very revolutionary. They are very patriotic. They look back on Mao with more reverence than most Chinese do."

Mao himself wrote a poem on the occasion of his swim at Wuhan, part of which goes like this:

Great plans are afoot:

A bridge will fly to span the North and South

Turning a barrier into a thoroughfare.

Walls of stone will stand upstream to the west

To hold back Wushan's clouds and rain

Till a smooth lake rises in the narrow gorges.

The mountain goddess, if she is still there,

Will marvel at a world so changed.

The aspirations for a grand dam are obvious even then (the mid-1950s). Winchester discusses how the control of water has been a perennial topic in Chinese philosophy, giving hydraulic engineering mega-projects a symbolic significance as well as a practical one:

It may seem odd to westerners that religion had any impact at all on hydraulics: but it is a measure of the peculiar importance of the country's waterways--as well as a reminder of the delicious strangeness of China--that its priests and philosophers did take so seriously the question of exerting control over them.

The views were diametrically opposed. Taoists, followers of what we might call a bohemian way of life, supported the building of only very low levees beside rivers and, generally speaking, letting them devise their own courses to the sea. Confucianists, who took a more rigid approach to governance and life in general, were also much more rigid in their approach to rivers: they believed that massive dikes should be built to corral the waterways along man-made courses and that the extra land thus freed should be intensively used for agriculture. They had a fatalist attitude to the disadvantages of their ideas: they accepted that their approach might well contribute to infrequent but massive flooding disasters--that their dikes would probably prevent moderate floods, but would likely break during serious flooding, causing occasional catastrophes. This, Confucian hydraulicists agreed, was an acceptable trade-off for the intervening periods of fertility and prosperity.

Heading up the river, Simon Winchester briefly notes cities that were, however briefly, the capital of China (or at least the seat of government for claimants). The sheer number of these between 1850 – 1950 illustrates how tumultuous this period was. The rulers had to relocate especially frequently during the Japanese occupation and the civil war that followed. Wuhan, for example, was the capital of one rival faction of the nationalists. Nanjing (a city weighted with tragic history) was the capital multiple times for multiple entities: the Taiping rebellion, the Nationalists under Chiang Kai-Shek, and the Japanese puppet/collaborator regime. Further upstream, Chongqing was the Nationalist capital during part of the war with Japan and also, briefly, during the Chinese civil war (as were Chengdu and Xichang). And these are only the ones within the Yangtze watershed—the full list is even longer.

From reading The River at the Centre of the World, I definitely got a much better sense of Chinese geography (within the Yangtze watershed, but that is a large and important part of the country as a whole). One part that stood out was Sichuan. It is a large and fertile inland basin, separated from central China by the mountain range that the Three Gorges cut through. Sichuan means 'four rivers' (compare to Mesopotamia meaning 'between the [two] rivers' or Punjab meaning 'five rivers'). This excerpt describes the rugged terrain between Yichang (where the mountain range begins, and near the location of the Three Gorges Dam) and Chongqing (a major city in the Sichuan basin, although it is now a province-level municipality instead of being part of Sichuan province):

Between Chongqing and Yichang is a range of mountains--jagged three-thousand footers all, outliers of the limestones and sandstones of the Tibetan hills that have here uncoiled their tentacles toward the eastern flats. A passerby will notice that once in a while the unfolded hills reveal a granite or a gneiss or a schist; mostly, though, the ridges are of ancient limestones, with softer shales and marls, or harder sills of volcanic rock, sandwiched between. The Yangtze escapes to the coast through them--she descends the 476 feet in just 140 miles of always fast, often turbulent and frequently raging river. In places the defile through which she runs is squeezed to a width of no more than 350 feet--and the great volume of water, which might have occupied half a mile of width before, which will spread languidly across a mile or more below, surges through it, slicing away the sides (and causing formidable landslips) and scouring away the river bed, so that the Yangtze here is one of the deepest rivers in the world.

(In metric units, the slope here is 0.65 metres per km). One of the legacies of this book is that Winchester travelled through these gorges by boat before they were flooded by the Three Gorges Dam. Before the construction of the dam, this section was navigable only with great risk and difficulty; prior to the 20th century trackers would pull ships up through the rapids but even with the advent of powered vessels it was no picnic.

To the West of the Sichuan basin lie even more formidable mountain ranges, the leading edge of the Tibetan plateau. I liked this description since I've personally driven to Denver from the eastern edge of Colorado a few times and can picture it well:

Driving across the Red Basin toward Yibin is rather like driving across Colorado to Denver: you begin in the morning, and the land is flat on all sides. In the late afternoon the sun, now directly ahead, inches down to reveal a long line of jagged hills: in America, the Rockies; here, the great ragged ranges of Sichuan and Yunnan, the granite and limestone temple guardians of Tibet.

The location of Yibin mentioned here is close to the limit of upriver navigation even today. It is located at a fork in the river, where the Min (which flows down from Chengdu) and the Jinsha (considered the main branch of the upper Yangtze) come together. The remainder of Winchester's journey was mainly by road, following the river as much as possible. He actually drove all the way from Chengdu to Lhasa (and the infrastructure in this part of China was minimal in the 1990s) then went a bit north to see one of the sources of the Yangtze. This overland part of the book is also interesting, but I'm trying to focus on the river portion for this review (which is definitely long enough as it is!).

The upper watershed is some of the most rugged terrain on the planet:

During its 3964-mile passage from the fringe of glaciers at the foot of Mount Gelandandong in Qinghai province, to the navigation buoy on the East China Sea, the Yangtze drops 17,660 feet--three and a third miles. Most of that drop occurs, as is the case with almost all rivers, in its first half. Between the glaciers and the distillery city of Yibin--a distance of 1973 miles, which happens to be almost precisely half the distance between the source and the sea--the river drops very nearly 17,000 feet--almost all of its total drop, in other words. ...

Above Yibin, every river mile of the Yangtze sees its waters falling an average of eight and a half feet. That is very steep by the standards of any major river. It is worth noting that the Colorado slides down along a similar gradient as it passes through the Grand Canyon--but manages to do so for only for 200 miles. The Yangtze, by contrast, keeps going down and down at the same average rate for fully 1900 miles.

(In metric units, the slope above Yibin is 1.6 m/km). The vicinity of Lijiang sounds like a good place to see some of this rugged scenery. Winchester describes the rapids of Tiger Leaping Gorge and the first great bend in the river just to the west of Lijiang. Edward Gargan also spent some time in this area, so I'll have a bit more to say about it further on in this post.

Before moving on to the next book, the afterword of the second edition is worth discussing. It looks back at Shanghai's growth in the decade since he took this trip and wrote the book:

Shanghai is today, and, without any stretch of the imagination, a truly incredible city--a multicolored fantasy world, a future city plucked straight from the pages of a 1950s Popular Mechanics, a vibrating, noisy, polluted, pulsating, sleepless Blade-Runnerish agglomeration of immense high-rise structures tricked out in the most gaudy of architectural styles, all brilliantly lit, all crammed with young professionals and hopefuls all participating, or doing their uneducated best to try to participate, in the wild joyride of a capitalisty dream-state that is today's China.

He felt that his prediction about Shanghai eclipsing Hong Kong was well underway by that point (2006). Another decade and a half later, and things have changed even more, as best I can tell from half a world away. Hong Kong is now not just feeling the pinch of competition from mainland port cities, but repression of its unique identity and political independence. At the same time, even Shanghai might now have reason to resent Beijing's domineering approach, for the way Covid was handled if nothing else.

On a semi-related note, I listened to a podcast interview earlier this year with Bo Shao, a Shanghaier who was one of the first Mainland Chinese students at Harvard, and later had a successful tech start-up. It really drove home how much Shanghai has transformed in only half a lifetime. And it contained a very thought-provoking quote about the legacy of the Cultural Revolution: "I would say this whole country has PTSD."

Edward Gargan's travelogue begins near where Simon Winchester's ends, on the Tibetan plateau (although in the western Chinese province of Qinghai rather than in the Tibetan region itself). For The River's Tale, he travelled down the Mekong. As with travel along the Yangtze, the journey in the upper watershed had to be conducted by road (and these roads sounded pretty sketchy in the late-1990s (the journey was in 1998 and the book was published in 2002) from his telling).

Here is how Gargan describes his route:

In a real sense, a Mekong journey is a voyage through the heart of Asia's complexity, amid a blizzard of languages, from the tongue spoken by the largest number of people in the world, Chinese, to a language shared by scarcely thousands, the Wa of southwestern Yunnan, across economies of utter deprivation and despair as well as those of affluence and promise, and among cultures under siege, as in Tibet, to those all but pulverized, as in Cambodia, to those content and self-confident, as in Thailand. Even the great thread that follows the river from its source to its exhausted release from Vietnam, the beliefs and practice of Buddhism, is in reality two great traditions that found their way from India on different historical currents. ...

The Mekong is no easy river. In swathes of Tibet and Yunnan, the river thunders through gorges, loud and violent; here it is untouchable, unreachable. A thousand miles to the south, it waltzes among hundreds of limestone outcrops and islands bushy with coconut palms, and pink-gray dolphins arch and blow in its gentle ripples. For China, the Mekong is a new source of energy, with two immense hydroelectric dams channeling its flow through massive turbines as the river lakes up behind the soaring concrete walls. For Laotians, it is still the country's principal transport route, a toilet for those along the river, and a bathtub and drinking water supply for the thousands of boatmen that ply it. In Vietnam, it is harbor and fishery, a web of canals and channels for vegetable sellers in wooden longboats, a prairie for duck herders in pirogues, the backroads of a good deal of the southern quarter of the country.

Even this brief overview shows some of this differences in writing style and topical emphasis from the other book. Which one is more to one's taste surely depends greatly on personality. Gargan's sentences are longer and have more adjectives (at one point he uses the word eleemosynary); they convey broad impressions rather than the types of details Winchester captures about rock formations and rapids (let alone quantitative details, for the most part). The focal topics in The River's Tale are the cultures along the Mekong and the traumatic history of the second half of the 20th Century; The River at the Centre of the World had more about geography, economic trends, and a longer historical view (reaching back at least to the middle of the 19th Century pretty frequently), for comparison. The history that he covers is palpably personal to Gargan: not only did he have a lot of work experience as a journalist in that region, he also was a conscientious objector during the Vietnam War and spent time in prison for it.

As mentioned, he began his journey on the Tibetan plateau, where the headwaters of the Mekong and many other mighty rivers originate (see the first figure in this post for an illustration of this):

Tibet is the nursery of most of Asia's great rivers. Near where we sat, at least in terms of direct-line miles--the journey is arduous--the sources of the Yangze, the Yellow and the Salween spill from this plateau. Asia's other major rivers, the Indus, the Brahmaputra and tributaries to the Ganges, tumble from the mountains elsewhere in Tibet.

After starting from some villages and towns in Qinghai, one of the first cities he visits is Chamdo/Qamdo. It sits at a confluence of the Mekong and was a historic cross-roads for the tea trade, with East-West traffic between Lhasa and Sichuan along with a route south to Yunnan.

In Tibet, and regions of neighbouring provinces like Qinghai and Yunnan where Tibetan culture is prevalent, Gargan was able to witness first-hand the rubble of some monasteries and other signs of suppression against monks:

Much of the trip ahead would be through fractured or dying cultures, through societies that had turned on themselves or been savaged by outsiders. Much of the trip, though, would be, I hoped, a window into how cultures draw the wagons into a circle, as it were, to preserve themselves.

from 1966 to 1976, politically crazed Red Guards, students and workers who outdid one another in violence and destruction in efforts to exhibit their fealty to Mao and his addled notion of a utopian Communist state, together with army troops, vandalized and then completely demolished the Sumtsanling monastery, reducing it to a Dresden-like field of building stumps and rubble. For the Tibetans here, the soul of their culture and civilization had been eviscerated.

In fact, it's not a stretch to say that Communists oppressing Buddhists is a recurring motif in his travelogue.

Most of his time in China was actually in Yunnan, which stretches along most of the border with Myanmar and all of the border with Laos. This certainly sounds like a beautiful area. Apparently the photos in National Geographic by Joseph Rock (a photographer and botanist mentioned in both books, as both authors travelled through Yunnan) were the inspiration for Shangri-la. This is also where rhododendrons grow natively. He also recommends a novel that is partially set in this general area of southwestern China: Soul Mountain by Gao Xingjian.

This region (i.e. Yunnan and western Sichuan) is home to a lot of Chinese ethnic minorities (such as the Yi, Wa, and Naxi/Nakhi peoples). While they can face a lot of challenges, Gargan was impressed with the efforts they had made to preserve their traditional culture. One example of this would be the preservation of traditional Naxi music, whose roots reach back to the Tang dynasty of over a millennium ago. In contrast, he felt (from years covering Asia as a foreign correspondent) that much of mainstream Chinese culture was not being preserved between the impact of the Cultural Revolution and a rush to modernize in more recent decades:

Perhaps because I spent so many years immersed in the study of early Chinese history, its society, literature, poetry, economic formation, I found myself on this trip gravitating toward China's remotest regions, those that still echoed of the past. Most of China, particularly the coast and the major cities, are unrecognizable as especially Chinese; for the most part they are undifferentiated replicas of what a modern city must seem to be--glass-walled towers, apartment blocks, well-paved boulevards. Beijing is the worst of these, with virtually every ancient neighborhood inside what used to be the boundaries of the old city wall (itself leveled by China's premier vandal, Mao Zedong) bulldozed to make room for office complexes, Lego-like apartment parks and eight-lane thoroughfares.

In contrast to the Yangtze, that the other book discussed in this post could title "the river at the centre of the world" without irony or hyperbole, the Mekong is much more marginal. At least in some aspects. It flows through remote parts of China, forms part of the border of Myanmar (a section of the border with China and the complete border with Laos), forms part of the border between Thailand and Laos in at least two sections, flows through parts of Laos and down the middle of Cambodia (and forms a short section of the border between them—at Si Phan Don which I'll have more to say about later), and finally has its delta in southern Vietnam. The delta aside, for most of its length, the banks of the Mekong have at least two of the following properties: separated by international borders, sparsely populated, or severely underdeveloped. This makes it well-suited for lawless activities like drug cultivation, and smuggling (including of weapons to resist the Japanese during the Second World War). The remoteness and liminality of the Mekong riparian also means that so far it has been very lightly industrialized. This limits certain types of pollution, although lots of raw sewage enters the river in its second half (the terrain is too rugged to have many riverfront towns in China) and the author also observed lots of random litter and flotsam like styrofoam.

Laos was a country where the author spent a fair bit of time on his trip. This was quite interesting, as it's not a place you hear much about. The impression that comes from The River's Tale is of a place that, even in the late 1990s, was basically left behind by the modern world. At the time (and possibly still although I haven't checked), it was the third largest producer of opium in the world (after Afghanistan and Myanmar), but something that stood out to me was that yields were significantly lower than in Myanmar/Burma (presumably due to less access to agricultural inputs and equipment). The contrast with Thailand was especially stark:

As we rocketed down the Mekong, glazing the surface of the river like a well-struck hockey puck, I found the contrast between Laos and Thailand so stark that it was jarring. Every mile of Thailand was hung with power lines, modern Japanese-made trucks glided over roads that were yet to see a pothole, a huge golf ball-like weather radar station perched on a bluff, lights blazed from riverfront restaurants. On our left, Laos was rugged, untamed, roadless, without power. Scraggles of bamboo huts on stilts hunkered along the river, and their occupants stared hopelessly at the bright lights just a quarter of a mile away.

Unlike the other Mekong countries, Thailand hadn't suffered under either colonialism or Communism, and it showed.

In Laos, Gargan spent time in the old royal capital of Luang Prabang, where he talked to students at Buddhist monasteries. They had rules for a simple and austere life (e.g. no eating after noon); they were also one of the only means for Laotian youth to get an education (and provided a generalized curriculum, not just studies in Buddhism). From there, he travelled to the capital of Vientiane; this journey had me shaking my head in several places. The water level was low but he insisted on travelling by boat, even when the boat captain or helmsman tried to pawn him off on other vessels or modes of transportation. He interpreted it as them not wanting to hold up their end of a deal that he'd already paid for, and to solve it the way you would any normal interpersonal conflict. For me, however, being more savvy about boats and rivers than the author (I've got an excerpt below that I think justifies this view), a much more likely explanation was that the river was dangerous to travel on at those water levels. If he wanted to risk it anyway, it would have been better to switch boats (or at least pilots) frequently so that the person steering would be familiar with the locations of submerged rocks and other hazards, but instead he tried to stick with one for this whole segment of the journey. And indeed there were at least a couple of hair-raising experiences with rapids along the way.

The next country on the Mekong after Laos is Cambodia. Before reaching it, there is a spectacular reach of the river where it runs along the border, known as Si Phan Don: Four Thousand Islands. It ends with a waterfall that is the largest in Asia by flow and the widest in the world before crossing the border into Cambodia. During the French colonial period, a portage railway (compare it to the never-completed Chignecto ship railway by Henry Ketchum and the marine railway on the Shubenacadie Canal) was built here, since the Mekong was otherwise navigable through most of French Indochina. Following the waterfall, the Mekong is only 117 ft above sea level where it enters Cambodia, so the river is generally gentler the rest of the way to the sea (an average slope of 0.07 m/km for those keeping track at home).

Looking back at his journey so far, Gargan reflected:

Unlike the Yangze River, China's greatest, which washes through the heart of a modernizing nation, the Mekong clips China's western flank, washing against peoples trying to preserve a way of life, a music, a language. So much of each of these cultures has been lost at the hand of Chinese Communist cultural imperiousness that I had the sense of visiting vanishing civilizations, a distinctly depressing feeling. And in Laos, too, I had seen what Communist rule had wrought, what ideological righteousness backed by force yields. Traveling in and observing a society that is hostage to fear and paranoia is deeply unsettling, an experience that tends to undermine all optimism. But Buddhism's flowering in such hostile terrain did offer some hope, some expectation that change could come even there.

In Cambodia, Communist rule had been even worse for the people, with the Khmer Rouge under Pol Pot committing auto-genocide in the late 1970s. Although they had been out of power for two decades by the time the author visited (driven out by a Vietnamese invasion) they had persisted as an armed force in northern Cambodia, and Pol Pot himself only died the year before the journey in this book.

Apparently the Khmer Rouge were obsessed with mass labour, harkening back to the glory days of Angkor. The River's Tale mentioned some of the prominent accomplishments of this labour (which were also in Steven Mithen's Thirst):

In the tenth and eleventh centuries, two mammoth lakes--five miles long and nearly two wide, known as the eastern and western baray--were dug to lubricate an intricate web of irrigation channels.

Pol Pot's regime didn't get anything nearly so productive done. And the things they did do were heavy to read about.

The last country on the itinerary was Vietnam, specifically the Mekong Delta region in the south.

Both the Pathet Lao and the Khmer Rouge found fertile ground in appeals to nationalism, to resistance against colonialism and the undeclared American war over their lands. And while both movements emerged victorious, they proceeded to assault their own cultures in a wholesale manner seen only in China, in Mao Zedong's vandalization of China's past. I left Laos more pessimistic than I did Cambodia, although neither country seemed likely to emerge from their own darkness anytime soon. I hoped that my travels through Vietnam's Mekong Delta, although just a fragment of the country itself, would reinstill some optimism in my view of the region.

Gargan compares the Mekong Delta region to the Netherlands, in both size and population. It was one of the most pro-American parts of the country during the Vietnam war, and many people from there left as refugees after the South fell. Saigon/Ho Chi Min city is adjacent to the Delta, and he used it as a gateway to the region. From his description, it was probably the most bustling and upward-trending place he visited on his whole trip. From Saigon/HCM, he travelled on a hydrofoil boat to Can Tho, the largest town in the Delta, then hired a local boat to tour around the distributaries and canals.

Unlike the other places he travelled, he didn't have to deal with police checkpoints in the Mekong Delta. Also, people seemed more connected with the outside world (e.g. having a cousin in New Jersey). In spite of the war a generation earlier, it seemed (from Gargan's impressions anyway) to be one of the least-scarred places along the Mekong:

But my conversations with those who were its victims also spoke of the costs of victory by the North; national unification brought with it peace, certainly, but it also brought a rigid authoritarianism that has stunted the lives of the Vietnamese. Even so, Vietnam is in no way the murky, paranoid place that is Laos, nor the traumatized land of Cambodia. It is a country, especially here in the south, that retains a sense of its culture and identity mixed with a yearning for the world beyond.

While he was touring around the Delta, one excerpt reinforced my perception (already stated above), that the author was not a technical chap when it came to boats. Fixing an engine is almost like magic—though very poetic!—the way he tells it:

I had no clue what had gone wrong, but Phuong opened a small kit of tools, more a collection of discarded screwdrivers and odd wrenches than an organized assemblage of engine-repair implements. He began unscrewing various bits of the engine, looking in tubes, tapping on its black epidermis like a practicing physician. He rummaged around some more in the toolbox until he found a piece of scrap metal that he proceeded to bend and cut. He held his handiwork up for inspection--it looked pretty much like a scrap of steel to me--and then proceeded to insert it into the engine. By now darkness had trampled over us, and I could see nothing as he conducted surgery on the engine. After some screwing and banging he raised his head, extracted his arms and keyed the engine. And to my utter astonishment, it turned over and fired up.

Having reached the South China Sea brings us full circle as far as the books are concerned. Before wrapping this post up, I have a few final topics I wanted to cover to bring the story up to the present.

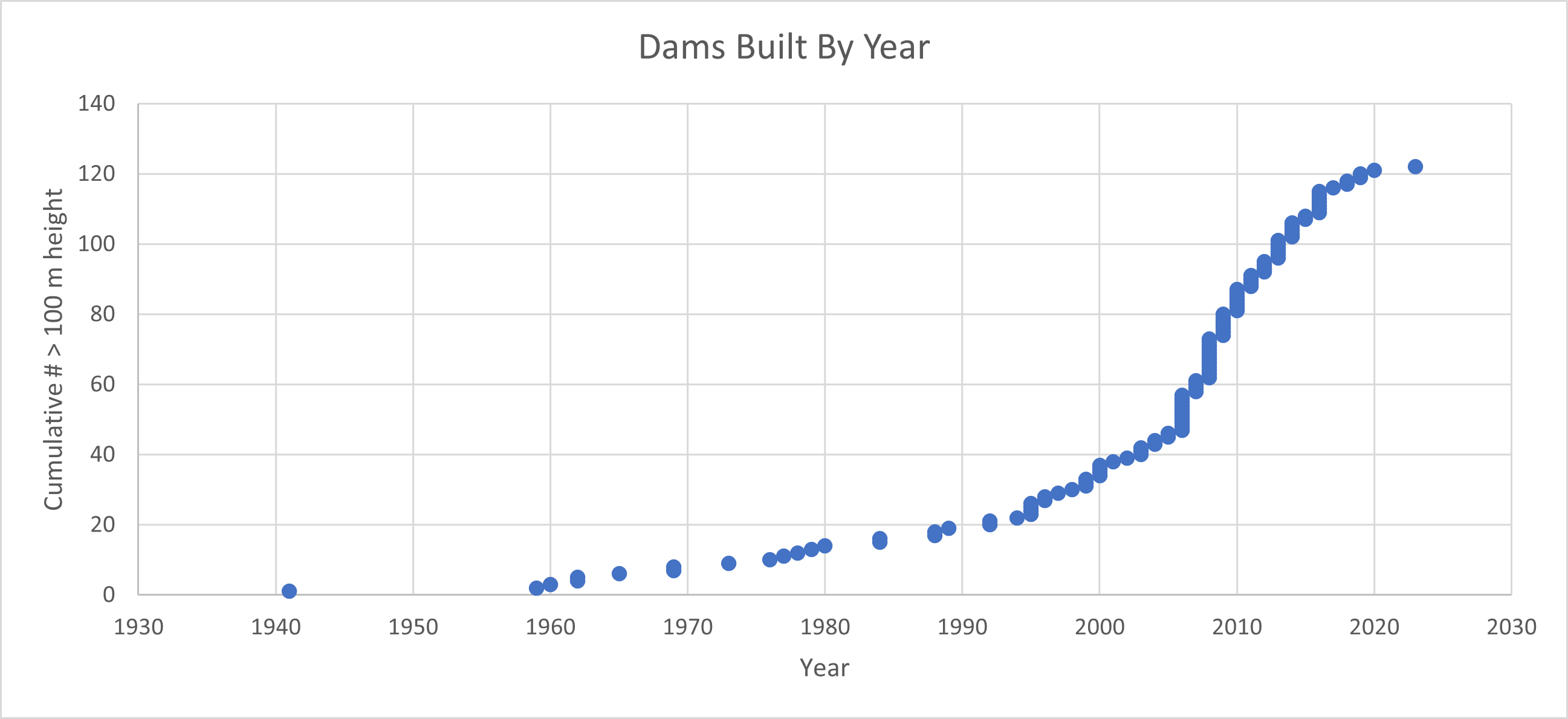

First of all, we need to talk about dams. Both authors noted a few dams that they passed in their journeys, and of course Winchester got to see the massive Three Gorges Dam under construction. However, the number of dams in this region has exploded since the start of the 21st century (i.e. shortly after these trips were taken). Here is a graph I made of the number of major dams in China, by year of construction:

This is not all of the dams in the country, only those greater than 100 metres in height. Of the 122 that exceed this threshold, 89 have been built since 2000. Many of these are in Sichuan (22) or Yunnan (26); there are 10 dams each on the Jinsha (upper Yangtze) and Lancang (Chinese name for Mekong), and many other dams on other Yangtze tributaries.

Currently, there is a drought in the region, which is partially exacerbated by the dams, and also makes them less useful at generating power.

The Salween River flows through the same terrain in Western China as the Mekong and Yangtze. However it is much less dammed so far. Here is a nice short documentary about kayaking and rafting on it:

I also found some videos of people whitewater kayaking on the Mekong in Laos and in Tibet (it doesn't say which rivers, but many of the ones there would be tributaries or the upper reaches of the Yangtze and Mekong).

Finally, this idea of planning a trip around travelling along the entire length of a river, from source to mouth, is kind of inspiring, and something I'd like to do some day if possible (also see this post).